Questions 22 through 31 are based on the following passage and supplementary material.

23. This passage is adapted from J. D. Watson and F. H. C. Crick, “Genetical Implications of the Structure of Deoxyribonucleic Acid.” Copyright 1953 by Nature Publishing Group. Watson and Crick deduced the structure of D N A using evidence from Rosalind Franklin and R. G. Gosling’s Xray crystallography diagrams of D N A and from Erwin Chargaff’s data on the base composition of D N A.

The chemical formula of deoxyribonucleic acid (D N A) is now well established. The molecule is a very long chain, the backbone of which consists of a regular alternation of sugar and phosphate groups. To each sugar is attached a nitrogenous base, which can be of four different types. Two of the possible bases—adenine and guanine—are purines, and the other two—thymine and cytosine—are pyrimidines. So far as is known, the sequence of bases along the chain is irregular. The monomer unit, consisting of phosphate, sugar and base, is known as a nucleotide.

The first feature of our structure which is of biological interest is that it consists not of one chain, but of two. These two chains are both coiled around a common fiber axis. It has often been assumed that since there was only one chain in the chemical formula there would only be one in the structural unit. However, the density, taken with the Xray evidence, suggests very strongly that there are two.

The other biologically important feature is the manner in which the two chains are held together. This is done by hydrogen bonds between the bases. The bases are joined together in pairs, a single base from one chain being hydrogenbonded to a single base from the other. The important point is that only certain pairs of bases will fit into the structure. One member of a pair must be a purine and the other a pyrimidine in order to bridge between the two chains. If a pair consisted of two purines, for example, there would not be room for it.

We believe that the bases will be present almost entirely in their most probable forms. If this is true, the conditions for forming hydrogen bonds are more restrictive, and the only pairs of bases possible are: adenine with thymine, and guanine with cytosine. Adenine, for example, can occur on either chain; but when it does, its partner on the other chain must always be thymine.

The phosphatesugar backbone of our model is completely regular, but any sequence of the pairs of bases can fit into the structure. It follows that in a long molecule many different permutations are possible, and it therefore seems likely that the precise sequence of bases is the code which carries the genetical information. If the actual order of the bases on one of the pair of chains were given, one could write down the exact order of the bases on the other one, because of the specific pairing. Thus one chain is, as it were, the complement of the other, and it is this feature which suggests how the deoxyribonucleic acid molecule might duplicate itself.

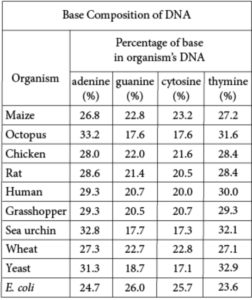

The table shows, for various organisms, the percentage of each of the four types of nitrogenous bases in that organism’s D N A.

Adapted from Manju Bansal, “D N A Structure: Revisiting the WatsonCrick Double Helix.” Copyright 2003 by Current Science Association, Bangalore.

Begin skippable figure description.

The figure presents a table titled “Base Composition of D N A.” The table contains 5 columns and 10 rows of data. The column heading for column 1 is “Organism” and there are 10 organisms listed. The column heading for columns 2 through 5 is “Percentage of base in organism’s D N A,” under which are four bases, adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. From top to bottom, the percentages of the 4 bases in each of the 10 organisms listed in the table are as follows.

Maize: adenine, 26.8%; guanine, 22.8%; cytosine, 23.2%; thymine, 27.2%.

Octopus: adenine, 33.2%; guanine, 17.6%; cytosine, 17.6%; thymine, 31.6%.

Chicken: adenine, 28.0%; guanine, 22.0%; cytosine, 21.6%; thymine, 28.4%.

Rat: adenine, 28.6%; guanine, 21.4%; cytosine, 20.5%; thymine, 28.4%.

Human: adenine, 29.3%; guanine, 20.7%; cytosine, 20.0%; thymine, 30.0%.

Grasshopper: adenine, 29.3%; guanine, 20.5%; cytosine, 20.7%; thymine, 29.3%.

Sea urchin: adenine, 32.8%; guanine, 17.7%; cytosine, 17.3%; thymine, 32.1%.

Wheat: adenine, 27.3%; guanine, 22.7%; cytosine, 22.8%; thymine, 27.1%.

Yeast: adenine, 31.3%; guanine, 18.7%; cytosine, 17.1%; thymine, 32.9%.

E. coli: adenine, 24.7%; guanine, 26.0%; cytosine, 25.7%; thymine, 23.6%.

End skippable figure description.

Question 22.

The authors use the word “backbone” in sentence 2 of paragraph 1 and sentence 1 of paragraph 5 to indicate that

Questions 22 through 31 are based on the following passage and supplementary material.

This passage is adapted from J. D. Watson and F. H. C. Crick, “Genetical Implications of the Structure of Deoxyribonucleic Acid.” Copyright 1953 by Nature Publishing Group. Watson and Crick deduced the structure of D N A using evidence from Rosalind Franklin and R. G. Gosling’s Xray crystallography diagrams of D N A and from Erwin Chargaff’s data on the base composition of D N A.

The chemical formula of deoxyribonucleic acid (D N A) is now well established. The molecule is a very long chain, the backbone of which consists of a regular alternation of sugar and phosphate groups. To each sugar is attached a nitrogenous base, which can be of four different types. Two of the possible bases—adenine and guanine—are purines, and the other two—thymine and cytosine—are pyrimidines. So far as is known, the sequence of bases along the chain is irregular. The monomer unit, consisting of phosphate, sugar and base, is known as a nucleotide.

The first feature of our structure which is of biological interest is that it consists not of one chain, but of two. These two chains are both coiled around a common fiber axis. It has often been assumed that since there was only one chain in the chemical formula there would only be one in the structural unit. However, the density, taken with the Xray evidence, suggests very strongly that there are two.

The other biologically important feature is the manner in which the two chains are held together. This is done by hydrogen bonds between the bases. The bases are joined together in pairs, a single base from one chain being hydrogenbonded to a single base from the other. The important point is that only certain pairs of bases will fit into the structure. One member of a pair must be a purine and the other a pyrimidine in order to bridge between the two chains. If a pair consisted of two purines, for example, there would not be room for it.

We believe that the bases will be present almost entirely in their most probable forms. If this is true, the conditions for forming hydrogen bonds are more restrictive, and the only pairs of bases possible are: adenine with thymine, and guanine with cytosine. Adenine, for example, can occur on either chain; but when it does, its partner on the other chain must always be thymine.

The phosphatesugar backbone of our model is completely regular, but any sequence of the pairs of bases can fit into the structure. It follows that in a long molecule many different permutations are possible, and it therefore seems likely that the precise sequence of bases is the code which carries the genetical information. If the actual order of the bases on one of the pair of chains were given, one could write down the exact order of the bases on the other one, because of the specific pairing. Thus one chain is, as it were, the complement of the other, and it is this feature which suggests how the deoxyribonucleic acid molecule might duplicate itself.

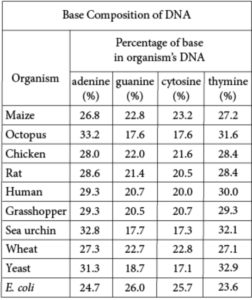

The table shows, for various organisms, the percentage of each of the four types of nitrogenous bases in that organism’s D N A.

Adapted from Manju Bansal, “D N A Structure: Revisiting the WatsonCrick Double Helix.” Copyright 2003 by Current Science Association, Bangalore.

Begin skippable figure description.

The figure presents a table titled “Base Composition of D N A.” The table contains 5 columns and 10 rows of data. The column heading for column 1 is “Organism” and there are 10 organisms listed. The column heading for columns 2 through 5 is “Percentage of base in organism’s D N A,” under which are four bases, adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. From top to bottom, the percentages of the 4 bases in each of the 10 organisms listed in the table are as follows.

Maize: adenine, 26.8%; guanine, 22.8%; cytosine, 23.2%; thymine, 27.2%.

Octopus: adenine, 33.2%; guanine, 17.6%; cytosine, 17.6%; thymine, 31.6%.

Chicken: adenine, 28.0%; guanine, 22.0%; cytosine, 21.6%; thymine, 28.4%.

Rat: adenine, 28.6%; guanine, 21.4%; cytosine, 20.5%; thymine, 28.4%.

Human: adenine, 29.3%; guanine, 20.7%; cytosine, 20.0%; thymine, 30.0%.

Grasshopper: adenine, 29.3%; guanine, 20.5%; cytosine, 20.7%; thymine, 29.3%.

Sea urchin: adenine, 32.8%; guanine, 17.7%; cytosine, 17.3%; thymine, 32.1%.

Wheat: adenine, 27.3%; guanine, 22.7%; cytosine, 22.8%; thymine, 27.1%.

Yeast: adenine, 31.3%; guanine, 18.7%; cytosine, 17.1%; thymine, 32.9%.

E. coli: adenine, 24.7%; guanine, 26.0%; cytosine, 25.7%; thymine, 23.6%.

End skippable figure description.